“It is not enough to acknowledge that American Indian music is different from other music and that the Indian, somehow, ‘marches to a different drum,’ as a way of paying obeisance to the unique culture of our Native American people. What is needed in America is an awakening and reorienting of our total spiritual and cultural perspective to embrace, understand, and learn from the aboriginal American what it is that motivates his musical and artistic impulses.”

– Louis Wayne Ballard1

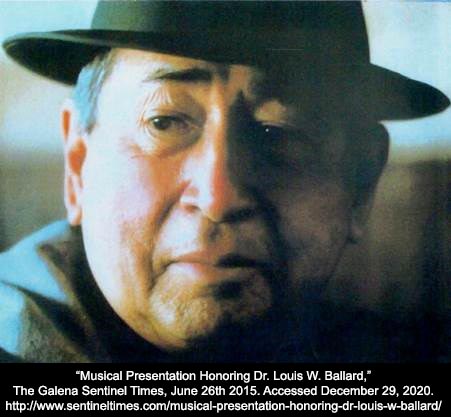

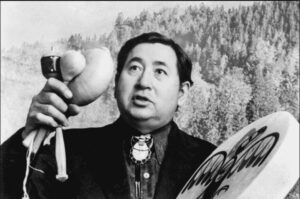

Louis Wayne Ballard, or Honga-nó-zhe (Stands With Eagles), was a composer, pianist, educator, ethnomusicologist, conductor, writer, singer, and dancer of Quapaw, Cherokee, French and Scottish descent. As a composer, Ballard sought to synthesize elements of Native American and Western classical music in an authentic and personal way. In his article titled “Cultural Differences: A Major Theme in Cultural Enrichment,” published in The Indian Historian in 1969, Ballard wrote:

“The expressiveness in art and in language of the American Indian has a universality possessing the power to touch and speak to every one of us in America, and everyone in the world. It can make a magnificent contribution to the mainstream of…world literature, music, education, architecture, design. The list is endless. The possibilities are unlimited.”2

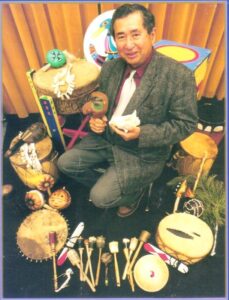

His vast compositional output includes 3 ballets, 4 cantatas, a one-act opera, and numerous works for piano, orchestra, and various chamber ensembles.3 Many of his works call for Native American percussion and/or woodwind instruments and derive inspiration from the songs, dances, ceremonial practices, and folklore of many Native American tribes. Ballard traveled across the country collecting and arranging numerous Native American songs, devising curricula for teaching these songs in schools, and incorporating them into his own compositional language.

Louis Wayne Ballard was born in 1931 on the Quapaw reservation, in Devil’s Promenade, Oklahoma.4 His first musical experiences came from attending powwows with his father, Charles Guthrie Ballard Jr., whose ancestry traces back to Cherokee Chief Joel B. Mayes, and early music lessons that included traditional American Indian songs taught at the piano by his mother, Leona, a descendant of Quapaw chief Louis Tallchief.5 His parents divorced before he turned 1, and after his mother remarried and moved to Michigan in 1935, Louis and his brother Charles went to live with their grandmother, Newakis, in Lincolnville, Oklahoma.6 After a serious accident in which Louis fell off of the bridge in Devil’s Promenade, his mother and grandparents, out of worry for the children’s safety, decided to send Louis and his brother Charles to the Seneca Indian School in Wyandotte, Oklahoma.7 In “This Song Remembers | Self-Portraits of Native Americans in the Arts” edited by Jane B. Katz, Ballard is cited recalling:

“When I was six, I was sent fifty miles from the reservation to attend a government-operated boarding school. This was in reality a brainwashing center for young Indians. There I was subjected to a reform-school “education.” We were punished severely if we spoke Indian Languages or danced tribal dances. I lived in barracks with 300 other boys. I had to make my bed well enough to bounce a quarter on it. I remember crying my eyes out because I couldn’t do it. Whenever one of us had a cold, we were lined up in a row and forced to take cough syrup–all from the same spoon. I saw my “gulag archipelago” in the first grade. I cried my way out of there” 8

Louis and Charles returned to their grandmother’s home, where Louis received regular piano, vocal, and tap dancing lessons. He later stated:

“Piano became my surrogate mother and father. It was reliable; It was always there…Periodically, we were sent to live with Mother in Wyandot, Michigan. We were often ostracized because we were Indian. The teacher would ask us to draw tom-toms and tomahawks, while others drew trees and puppies. After school, the white students often chased us and threw rocks…. I continued to live in two worlds.” 9

During his high school years, Ballard excelled at music, art, sports, and academics, winning prizes in local piano competitions, having original paintings exhibited at the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and being named captain of his high school football and baseball teams at the Bacone Indian Institute, where he graduated as a valedictorian in 1949.10 He briefly attended the University of Oklahoma, and Northeastern Oklahoma A&M, before being recruited by Hungarian composer Béla Rózsa, a former student of Arnold Schoenberg, to attend the University of Tulsa. There, he earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts in Music Theory, Bachelor of Music Education in Vocal and Instrumental Music, and Master of Music in Composition.11

Throughout his life, Ballard worked tirelessly to break the stereotypes perpetuated about Native American music by the Indianist movement of the late 19th/early 20th century as well as by Hollywood movies, which he thought reduced the vast and complex landscape of Native American music to pentatonic scale melodies and a few easily recognizable rhythmic patterns. In a lecture entitled “The Cultural Milieu and American Indian Music” that Ballard gave in 1960 at the First Indian Festival of the Arts in La Grande Oregon, he articulated several aesthetic characteristics prevalent in Native American song, and explained that his aim was not to imitate Native American music, but rather to channel its essence in his compositions:12

“What I seek is a reincarnation of the character and spirit of the aboriginal music in standard notation. The avenue I have chosen is modified atonality, based on the 12-tone system as devised by Arnold Schoenberg.” 13

In 1963, the year after graduating with his master’s degree, Ballard attended the Aspen music festival where he studied composition with Darius Milhaud and met his second wife, pianist Ruth Doré.14 While at Aspen he composed Four American Indian Piano Preludes, a work that blends characteristics of Native American music with Western modernist idioms, including bitonality and elements of 12-tone technique.15 Courtney Crappell’s insightful dissertation “Native American Influence in the Piano Music of Louis W. Ballard” identifies several characteristics of this work that seem to be influenced by Native American music, including the use of ornamented, rhythmically free melodic passages evoking Native American flute melodies;16 “terrace descending” melodic patterns in which the melodic line descends to a repeated pitch;17 the use of repeated notes with intermittent accents found in Powwow drumming;18 the frequent use of polyrhythms19; gradual intensification of energy in dance-like sections;20 doubling of melodies at the octave, and the emphasis on linear musical textures.21

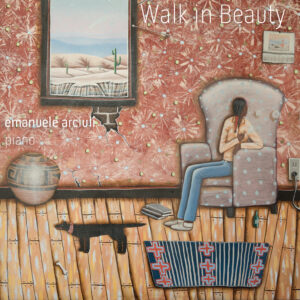

After hearing these preludes, Darius Milhaud exclaimed “Louis, now you are a real composer!”22 Despite the fact that the Four American Indian Piano Preludes were among Ballard’s most frequently performed works during his life, Emanuele Arciuli’s recording of the Preludes, available on Inova Records, is the only commercially-available recording of the work known to date. Here is an outstanding live recording of Arciuli playing the work at Bard College in October 2017.

Right after graduating from University of Tulsa in 1962, Ballard was hired as a founding faculty member and Performing Arts Director at the Institute of American Indian Arts [IAIA].23 The following year at the IAIA, he formed the E-Yah-Pah-Hah Indian Chanters, a vocal ensemble that sang traditional Native American songs arranged by Ballard. In 1970, he formed the American Indian Creative Percussion Ensemble at the IAIA, which became the first all-American-Indian group to perform at the National Folk Festival at Wolf Trap Farm in Virginia.24 Throughout his illustrious career as an educator, Ballard served as director of the Office of Music Education at the Bureau of Indian Affairs [BIA], where he was also in charge of planning the curricula for 276 schools in the BIA’s network;25 conducted workshops for children and trained teachers throughout reservation areas;26 taught courses in Native American music at the University of New Mexico and William Jewell College;27 and gave lectures on Native American music at various institutions in Europe and the United States.28

His compositions have often been played in educational contexts. For example, Why the Duck Has a Short Tail for orchestra and narrator, which is based on a Navajo legend about the creation of the mountains by the first man on the continent, was performed extensively in children’s programs, receiving over 100 performances throughout the world, including at least 18 performances at the Kennedy Center.29 Ballard’s woodwind quintet Ritmo Indio, the second movement of which is based on a Tlingit paddling song and utilizes a Sioux courting flute, was performed by the Dorian Quintet in 150 concerts for Native American children in New Mexico and Arizona.30

Ballard’s dedication and passion for education extended beyond his teaching and administrative activities. Throughout his life, he published several books and other educational materials on Native American music, which include his transcriptions of numerous traditional songs, audio recordings of him singing and teaching the songs, diagrams of traditional dances, explanations of cultural practices and historical events, descriptions of traditional musical instruments, discussions of Native American musical aesthetics, and pronunciation guides for Native American languages.31‘32 One of his most significant publications is American Indian Music in the Classroom (1973), a manual for music instructors that includes 26 songs from 22 different tribes.33 Referring to its updated version, published in 2004 as “Native American Indian Songs Taught by Louis W. Ballard,” he stated:

“This guidebook means a lot to me, and to Americans everywhere, including Native Americans…This is America’s cultural heritage. I want the tradition of our songs and our music to live on, and the best way to do that is to teach all teachers how to teach them. Simple as that.”34

Throughout his life, he remained committed to the study, preservation, and continuation of Native American culture. He was one of few people in the world fluent in the Quapaw language;35 he was a member of the War Dance Society of the Quapaw tribe; he won multiple awards as a tribal singer and dancer at powwows and at the Anadarko American Indian Exhibition;36 he worked to improve the representation of Native Americans in film through his own company, First American Indian Films;37 and he was a founding member of the First Nations Composers Initiative, which is “dedicated to the encouragement and propagation of American Indian music and musical traditions in all its forms.”38

Ballard’s music has been performed on every continent except Antarctica, by major orchestras and conductors including the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, Marin Alsop, Zubin Mehta, and Dennis Russell Davies, and at venues such as Carnegie Hall, Alice Tully Hall, The Kennedy Center, and Beethovenhalle. He received numerous commissions from establishments and individuals including Dennis Russel Davies, St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, American Composers Orchestra, Tulsa Philharmonic Orchestra, the Ensemble of Santa Fe, Harkness Ballet, and the Indianapolis Symphony.39

Over the course of his career, Ballard received four National Indian Achievement Awards, the Distinguished Service Award from the U.S. Central Office of Education, a citation in the U.S. Congressional Record, a Lifetime Musical Achievement Award from First Americans in the Arts, the Cherokee Medal of Honor, honorary doctorates in music from the College of Santa Fe and William Jewell College, five grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, grants from the Rockefeller Foundation and the Ford Foundation,40 the first Marion Nevins MacDowell Award for chamber music,41 and the edPRESS Award for Educational Journalism.42 His Desert Trilogy for mixed octet (clarinet, trumpet, trombone, timpani, percussion, violin, viola and cello) and Fantasy Aborigine No. 4 Xactoe’oyan, Companion of Talking to God were nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in Music.43

If this impressive list of achievements has inspired you to search for recordings of Louis Ballard’s music, unfortunately you will be disappointed to find very few. The vast majority of his compositions, including the above-mentioned Pulitzer-nominated works, have not been commercially recorded or are no longer readily available. There is only one full-length album of his works, entitled Ballard, which he released on cassette in 1987 through his own label, WAKAN: Native American Classics. The album includes recordings of Incident at Wounded Knee for chamber orchestra, Cacéga Ayuwípi for percussion ensemble, and Music for the Earth and the Sky for percussion ensemble.44 Incident at Wounded Knee was written in response to two historical events – the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890, and the protests by Native Americans at Wounded Knee from 1973-74.45 Ballard writes of the work:

“A series of musical episodes depict the emotional procession toward the town, the state of the souls in torment, and the violent conflict. The work culminates in musical and dance forms affirming the essential spirituality of Native American people. Incident is not a political work, but it drew a strong reaction from oppressed peoples when it was played in Poland and Czechoslovakia, as well as the cities of Western Europe.” 46

The recording of the work can be found here.

An archived live concert recording from Arizona State University’s Visiting Composer Series in 1992 represents the largest currently available collection of audio recordings of Ballard’s music. The concert includes performances of his Katcina Dances for cello and piano, Ritmo Indio for Woodwind Quintet, Desert Trilogy for mixed octet, City of Light for piano played by Ballard himself, Siouxiana for woodwind choir, as well as an inspiring speech by Ballard entitled “The prophecy of Dvorak: one hundred years later.” These recordings can be found here: https://repository.asu.edu/items/7668

The most comprehensive source of information on Louis W. Ballard’s life and works available to date is Dr. Karl Erik Ettinger’s PhD Dissertation “Louis W. Ballard: Composer and Music Educator,” available via University of Florida Digital Collections (http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UFE0046553/00001).

Our research on Louis Ballard’s work has brought us in touch with the stellar Italian pianist Emanuele Arciuli, an important advocate for contemporary American piano repertoire, who is the dedicatee of compositions by numerous American composers, including George Crumb, Raven Chacon, Kyle Gann, John Luther Adams, Brent Michael Davids, Morton Subotnick, Michael Daugherty, Martin Bresnick, and Louis Ballard. Emanuele Arciuli, who knew and worked with Louis Ballard, graciously agreed to speak with us about the composer.

* * *

Excerpts from Kaleidoscope MusArt’s interview with Emanuele Arciuli on October 14, 2020

KMA : How did you meet Louis Ballard?

E.A : So, I think, twenty years ago…I read an important book that perhaps you should know, that is the “Guide to the Pianist’s Repertoire” by Maurice Hinson. It is a book that contains a lot of piano music, of course, by composers from all over the world. I was not yet totally involved in American music, not as involved as I am now, but I was starting my interest for American music, and I was really surprised when I discovered that there was a Native American composer – a Quapaw-Cherokee composer – of classical piano music. Of course, the internet was not that strong and we still had to order CDs, and also reaching the sheet music was not that easy. So I had the idea to find Louis Ballard’s phone number in the white pages, and I just called him. He was kind but very suspicious with me, because he was many times disappointed with white people and with people in general. And so he told me “OK, I can send you my music but you have to buy it.” And of course I paid for the four scores he sent to me – or the three – I don’t remember how many he sent. But anyway, he also sent a song for female voice and piano. Two years later, in 2004, when I was already involved in American music and also started my strong interest for Native American painting, visual art – I collect Native American visual art and I also wrote a book, in Italian, on the history of Native American paintings – I organized a little concert with also an exhibition of a Native American painter, and I performed Ballard’s American Indian Preludes, and also performed songs by Ballard with Metropolitan opera star Raina Kabaivanska. We sent him the video, and he was totally amazed with – I don’t know if really with the performance – but for sure he understood that I was sincere and I was loyal in my interest for his music – and he became the most generous and most open person ever. He invited me to Santa Fe that then became perhaps my favorite place in the world, along with Albuquerque, New Mexico. I was there for the first time in 2005, and he invited me for lunch, cooking bison with Italian wine, and announcing that he was already composing a piano concerto for me. We went to his studio and he just played on the computer the first movement – some sketch of the first movement of the piano concerto. My English was even worse than my English today, and so I didn’t understand everything he told me. What a pity, because he also told interesting stories. But, he was already sick, he had cancer, and of course we started to be in touch; he wrote me letters that unfortunately I lost, because you know that now, with email, if the provider doesn’t work anymore, you can really lose a lot of letters – you should print them, but I didn’t, unfortunately, so I have just something. Anyway, he continued to compose the concerto and he was obsessed by the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra commission. He was not totally sure about them and about the conditions, and sometimes he called me in the night at 3 or 4. Perhaps he just was not totally aware about the hour, and so he called me several times. Unfortunately he died in 2007, so the concerto was completed by another Native American composer, Brent Michael Davids, and performed in 2008. But, my memory of Louis is very strong. In fact, today, or actually tomorrow, my new book, The Beauty of New Music, will be available in bookstores, and in the acknowledgment I mention Louis as one of the four cardinal points in my personal and musical life along with George Crumb, Frederic Rzewski, and Joel Hoffman… I met him only one time in 2005, but I am devoting a lot of energy to his music and his figure because, in my opinion, he deserves more attention…

KMA: When you read about Louis Ballard in Maurice Hinson’s book, was he the first Native American composer that you learned of?

E.A: Yes. He was also the only Native American composer in the book. Then, when I started to investigate about Native American Music, I discovered other composers, and basically all of them have composed piano music for me. So, Brent Michael Davids is one of them. Raven Chacon is another good composer that Louis Ballard introduced to me, because he invited me to a concert in Albuquerque, Keller Hall, which was a two composer portrait, the old and the young – so Louis Ballard and Raven Chacon – and Raven also is a very very talented composer. Then Barbara Croall, she’s Canadian and she also has composed a piece for me, and then I started also to collaborate with a very very famous Native American flutist, Carlos Nakai, and we played in duo in Arizona and also in Italy some time, and in New Mexico, having a lot of fun together. Also there are other composers – Jerrod Tate for instance – I have plans with him. And George Quincy, another composer based in New York, also composed piano music for me. But, of course, perhaps you know that I’m a champion of American music, and more than 30-40 composers composed music for me including Michael Torke, Michael Daugherty, William Bolcom, John Luther Adams, Martin Bresnick, Peter Garland, Milton Babbitt, Frederik Rzewski, Aaron Jay Kernis…So, despite my English, I’m like an American pianist in some way but living in front of the Adriatic Sea.

KMA: You mentioned there were three or four scores that Louis sent to you. Other than Four American Indian Preludes and the song that you mentioned, what other works did he send you?

E.A: Yeah, he has composed The Cities – City of Light, City of Fire, and City of Silver. I have not performed those pieces. They are very demanding, also very virtuoso, and I would like to do it, but I have not yet performed that music. But also, when we became friends, he gave me a lot of music for free, including a selection from his ballet The Four Moons. He composed a ballet for four étoiles. You know perhaps the étoiles, Native American étoiles, who became very famous all over the world, and there is a piano transcription of this ballet. I love the transcription of The Four Moons – Four Variations, and I performed those pieces in Santa Fe, and recorded the Osage Variation on Walk in Beauty too. But the most – famous is not correct – but the most performed piece is perhaps the Four American Indian Piano Preludes. That is also his first one for piano. Also, he gave me the Katcina Dances for cello and piano, and I played selections of those, and a violin sonata, Rio Grande Sonata, that exists in two versions – one for solo violin and one with piano, which was added later, like Schoenberg did with his Fantasy for piano and violin.

KMA: Did you have much of a chance to play Louis’s music for him and have him coach you or give you input on his music, and if so, what was that experience like?

E.A: So, I didn’t play his music for him except the recording I sent to him before we met. But, he showed me at the piano how he wanted the piano music performed. Also he sent me a letter, a very detailed letter that of course was lost because of a computer provider change, in which he sent me a lot of corrections of the piano preludes. But I know two things: the first is that I am absolutely sure that Ballard was very open to proposals and to contributions of performers if he trusted them. And I’m sure that if we had worked together on the preludes, perhaps, of course, he could have changed something or modified something…he did not have an editor or some person who could correct mistakes…when he invited me to the Albuquerque recital with Raven Chacon and himself, there was a young pianist, Pamela Pyle, who is adjunct professor at Albuquerque, Collaborative Piano, I think – and it was not a recital, it was like a lesson in public in which he told her how to play his music. Of course sometimes it was strange because his intentions were not totally clear, and for instance when we were at his home, playing some bars of his piano preludes, he played one bar, and he told me: “I don’t want it this way, I want it this other way” – he played both ways, but they were almost the same. So it was difficult to understand what he really wanted sometimes. He was very energetic and very furious but sometimes was not clear enough. But, I’m sure that anyway, if you are a musician and if you play his music deeply and with a strong intention, I’m sure that he would approve your vision. What a pity that we had not enough time working together!

KMA: How would you describe Louis Ballard as a person?

E.A: Oh, he was absolutely lovely! He was not really sweet; he was very proud, he was very strong, but also very generous. It was the first time in New Mexico for me. Then I visited New Mexico at least 15, 20 times since, and now I know the area very well. But it was the first time, and for instance he suggested a lot of interesting places to visit in Arizona and New Mexico, and he told me a lot of stories about his childhood, about his mother, and about the school. But of course because of my English it was very hard for me to ask more questions about politics, about his teaching experience, and about a lot of things. I am a close friend of Dennis Russell Davies, who is a very established conductor, and he did a lot for Louis Ballard, commissioning five pieces from him. Also, the Incident at Wounded Knee was commissioned by Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Dennis Russell Davies conducting, and perhaps he should know more about him as a person. I will ask also because I am approaching a new book – I’m a pianist, I’m not a writer, but anyway I like to write books – and my new book is just about American mavericks. So, composers like William Duckworth, or Peter Garland. Some are not famous even in the States. One will be for sure Louis Ballard, so I will collect stories and I will try to know more about him.

* * *

We look forward to Emanuele Arciuli’s upcoming book, and we hope that Louis Ballard’s work will become much better known.

Authors: Maria Sumareva & Andrew Rosenblum

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Bibliography and References:

Ballard, Wayne Louis. “Louis Ballard, Quapaw/Cherokee Composer.” In This Song Remembers: Self-Portraits of Native Americans in the Arts, edited by Jane B. Katz, 132-138. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980.

Ballard, Louis W. American Indian Music for the Classroom. [Phoenix, Ariz.]: Canyon Records, 1973.

Crappell, Courtney J. “Native American Influence in the Piano Music of Louis W. Ballard.” The University of Oklahoma, Norman, 2008. PQDT Open – ProQuest <http://pqdtopen.proquest.com/#viewpdf?dispub=3355760>.

Ettinger, Karl Erik. “Louis W. Ballard: Composer and Music Educator.” PhD diss., University of Florida, Gainesville, 2014. University of Florida Digital Collections <http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UFE0046553/00001>.

Idealist. “First Nations Composer Initiative.” Accessed December 28, 2020. https://www.idealist.org/en/nonprofit/08b18730b3c041b0b5c1caf714f68546-first-nations-composer-initiative-saint-paul

- Karl Erik Ettinger, “Louis W. Ballard: Composer and Music Educator” (PhD diss., University of Florida, Gainesville, 2014), 31-32, University of Florida Digital Collections <http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UFE0046553/00001>

- Courtney J. Crappell, “Native American Influence in the Piano Music of Louis W. Ballard” (DMA doc., The University of Oklahoma, 2008), 5, PQDT Open – ProQuest <http://pqdtopen.proquest.com/#viewpdf?dispub=3355760>.

- Ettinger, “Louis W. Ballard,” 337-351.

- Ibid., 49-50.

- Ibid., 51-52.

- Ibid, 53.

- Crappell, “Native American Influence,” 122.

- Louis Wayne Ballard, “Louis Ballard, Quapaw/Cherokee Composer,” in This Song Remembers: Self-Portraits of Native Americans in the Arts, ed. Jane B. Katz (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980), 135.

- Ibid., 136.

- Ettinger, “Louis W. Ballard,” 56, 59.

- Ibid., 64-66.

- Ibid., 69, 71.

- Ibid. 72.

- Ibid., 79.

- Crappell, “Native American Influence,” 28, 36.

- Ibid., 29, 31.

- Ibid., 32.

- Ibid., 33.

- Ibid., 52.

- Ibid., 34.

- Ibid., 53.

- Ibid., 3.

- Ettinger, “Louis W. Ballard,” 75, 334.

- Ibid., 142, 161.

- Ibid., 191, 127.

- Ibid., 29.

- Ibid., 231.

- Ibid., 86, 171, 182, 183.

- Ibid., 125, 133, 151.

- Ibid., 122, 242.

- Louis W. Ballard, American Indian Music for the Classroom (Phoenix: Canyon Records, 1973), 8.

- Ettinger, “Louis W. Ballard,” 40-44.

- Ibid., 43.

- Ibid., 235.

- Ibid., 239.

- Ibid., 60-61.

- Ibid., 120.

- “First Nations Composer Initiative,” Idealist, Accessed December 28, 2020, https://www.idealist.org/en/nonprofit/08b18730b3c041b0b5c1caf714f68546-first-nations-composer-initiative-saint-paul

- Ettinger, “Louis W. Ballard,” 49-236.

- Crappell, “Native American Influence,” 25-26.

- Ettinger, “Louis W. Ballard,” 127.

- Ballard, “Quapaw/Cherokee Composer,” 133.

- Ettinger, “Louis W. Ballard,” 344, 347.

- Ibid., 208.

- Ibid., 167-168.

- Ibid., 169.