“Roque Cordero remains to this day the premier composer of art music from his native Panama,

known for his trademark synthesis of high-modernist techniques with the rhythms of folkloric dance.”

– Jeremy Orosz 1

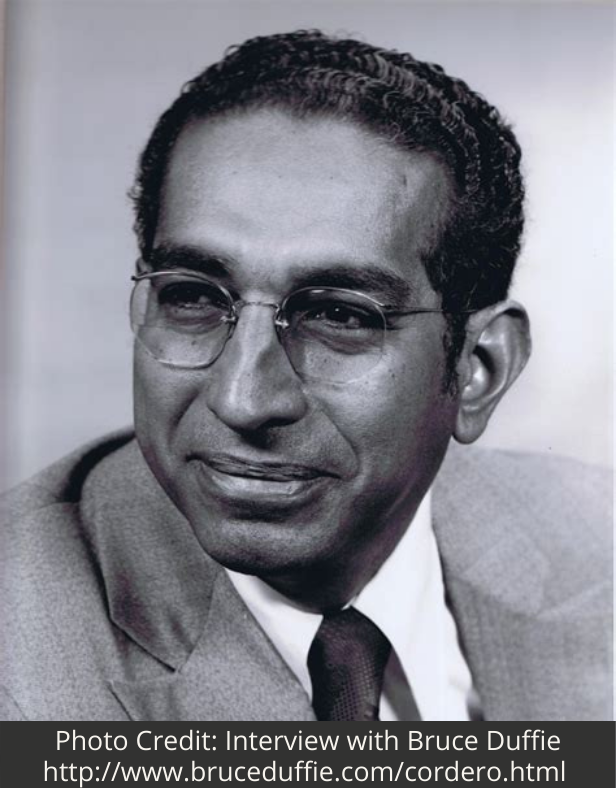

Regarded today as one of Panama’s finest composers, Cordero became a composer through a series of fortuitous circumstances.2 While at a vocational school studying to become a plumber, a teenage Cordero saw a group of students raising their hands and decided to raise his. He did not realize that the music teacher at the school was looking for students to learn how to play newly acquired string instruments! Thus, by accident, he began his studies in violin, and soon after had picked up the clarinet, joining the school’s orchestra and band. He taught himself solfege and harmony, and picked up on orchestration by working as a copyist for the Fireman’s Band in Panama city.3 His formal musical training began in 1943, when at the age of 25, he moved to the US and pursued a degree in music education at the University of Minnesota, while also studying composition with Ernst Krenek at Hamline University. With Krenek’s guidance, Cordero mastered the 12-tone technique, which he synthesized, in his own works, with Panamanian musical elements. 4

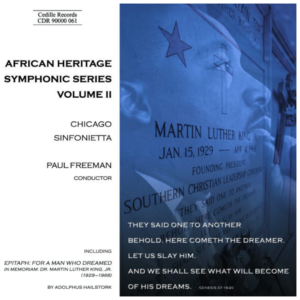

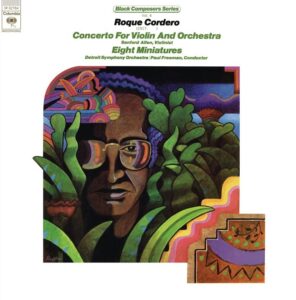

Ocho Miniaturas [eight miniatures] for small orchestra written in 1948 is an early example of this newly-formed synthesis, which would become a trademark of his style. The work is infused with the Latin American rhythms of the danzón, the mejorana, the punto, and the pasillo.5 We invite you to listen to the historic recording of Ocho Miniaturas by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra conducted by Paul Freeman, released on Columbia Records’ Black Composers Series in 1987.6 In 2001, another recording of the work was released on Cedille Records’ African Heritage Symphonic Series – Vol. II, performed by Chicago Sinfonietta under the baton of Paul Freeman.

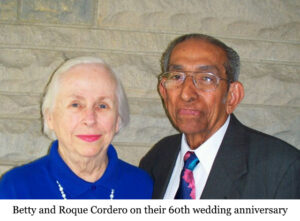

After graduating from Hamline University, in 1947 Cordero went on to study conducting with Leon Barzin in New York for two years.7 Between 1947 and his return to Panama in 1950, Cordero married his classmate Betty Johnson; met Henry Cowell, Aaron Copland, Edgard Varèse, Alberto Ginastera, and Juan Orrego-Salas8 and received a Guggenheim fellowship for composing and conducting.9 In 1950, he returned to Panama, committed to sharing the experience he gained in the U.S. with the next generation of Panamanian composers.10 During the next 16 years in Panama, Cordero served as a professor of composition at the National Conservatory; director of the same institution between 1953-1964; and conductor of the Panama National Orchestra from 1964 until his return to the U.S. in 1966.11 It is during this period that Cordero completed his Symphony no. 2 in One Movement, which, in 1957, won the second prize at the Second Festival of Latin American Music in Caracas. In an interview with Bruce Duffie, Cordero says about the piece:

“It is a very strong piece, and very, very personal. It’s a unique structure that I haven’t found before or after. It’s a two-sonata form, one inside the other, in a one single-movement piece. It’s a piece that moved the audience when it was premiered in Caracas. Gilbert Chase wrote that I was proof that a so-called ‘forbidden’ twelve-tone technique wasn’t an obstacle between something that a man wants to say, and an audience avid to hear it. They didn’t have to know there was twelve-tone technique. They were just hearing music. It doesn’t have the conventional closing on a perfect cadence. It ended on a dissonant chord, and yet it doesn’t disturb anybody, because it’s handled with such refinement that you feel satisfied.”12

During the 16 years he spent in Panama, in an effort to elevate the level of education and performance at the National Conservatory and National Orchestra, Cordero faced a lot of obstacles and frustration.13 It is during these difficult years that he conceived the Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, which was completed in 1962, upon receiving a commission from Serge Koussevitzky Music Foundation. This large-scale masterpiece took Cordero several years to complete. In the interview with Bruce Duffie, Cordero shared that, after having sketched the first movement, having completed the second, and being at the start of the third, he no longer liked what he had written. He then destroyed the previously-written material and started anew.14 In the same interview, Cordero explains: “I don’t rush any piece. The Violin Concerto took me several years to write.[…] Every little thing takes me a long time. I look, and if I find that it’s not exactly what I intended to do, I don’t give the piece to you to play.”15

The orchestration of the piece elegantly highlights its emotional architecture, exploring varied expressive, timbral, and textural palettes. The second movement is set for a chamber ensemble consisting of solo wind and low string instruments, while the outer movements are richly-scored for the full orchestra. In 1974, Cordero’s Violin Concerto was awarded the Koussevitzky International Recording Award.

It was recorded the same year by  Sanford Allen (violin) with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra conducted by Paul Freeman, in the above-mentioned historic Columbia Records release, which we invite you to listen to here.

Sanford Allen (violin) with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra conducted by Paul Freeman, in the above-mentioned historic Columbia Records release, which we invite you to listen to here.

In 1964 Cordero quit the post of the director of the National Conservatory in order to conduct the National Orchestra. He fought in vain to obtain the orchestra’s proper funding from the state, and his ongoing frustrations with his circumstances in Panama led him to accept the position of assistant director of the Latin American Music Center and teacher of composition at Indiana University in 1966. He spent the rest of his life in the U.S., having served as a music editor at Peer Southern publishing company between 1969 and 1972, and professor of composition at Illinois State University in Normal, IL from 1972 until his retirement in 2000.16

The next two works, of contrasting scale and significance, were both written after Cordero’s emigration to the U.S.

Composed in 1988, Rapsodia Panameña [Panamanian Rhapsody] for solo violin subtly infuses Panamanian elements into its musical fabric, while oscillating between angular atonal passages, intense lyricism, and fiery rhythmic outbursts. In an interview with T.C. Towsend published in 1997, Cordero speaks on the relation of the European and Panamanian or Latin American influences in his music:

“I had to integrate technical elements from Europe…but that technique has to be true for myself to express something that has to be completely personal. I am not necessarily quoting from the Panamanian folk song because I have very seldom quoted directly from Panamanian folk song, but I do use rhythmic elements and some melodic design that can be found there without being any one in particular.”17

Here is a refreshing and boisterous rendition of Rapsodia Panameña, performed by violinist Rachel Barton Pine on Cedille Records’ release, Capricho Latino.

It is noteworthy that the work Cordero considered to be among his most ambitious, his Cantata para la Paz [Cantata for Peace], written in 1979 and commissioned by the National Endowment for the Arts, received its world premiere nearly four decades after being composed and nearly one decade after Cordero’s death. In the interview with T.C. Towsend, Cordero explains that the Cantata was written “to honor four men who spoke of peace and were victims of violence: Abraham Lincoln, Mahatma Gandhi, John F. Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr., but also dedicated to the memory of all men, women and children who died in the name of peace.”18 In the same interview, he states:

“I had a musical message of peace in which I found similarities between their ideas of peace and my own. All of them were speaking against violence—that was what linked the four of them together. But mostly it was just a personal expression, it didn’t have anything to do with the Civil Rights movement or the Civil War…. it was simply the idea of peace.”19

In her introductory remarks before the work’s world premiere at Texas Christian University, musicologist and Cordero’s biographer

Dr. Marie Labonville quotes Cordero as follows:

“My idea of peace is not the quiet period of rest between wars, nor the dangerous peace brought about by the presence of heavily armed forces staring at each other across the no man’s land. My cry for peace, as utopian as it may be, is for an inner peace, which would allow mankind to embrace all humanity, regardless of color, creed, or sex, in a universal chain of love and understanding, helping to eliminate famine and poverty, building a world in which children of all places can play and laugh and grow without the terrifying shadow of death menacing their tomorrows.”20

We invite you to listen to the world premiere performance of Roque Cordero’s Cantata para la Paz by bass-baritone Nate Mattingly with the TCU Symphony Orchestra and TCU Concert Chorale, conducted by Dr. German Guttierez at Texas Christian University in October 2017, which to our knowledge is the only recording of the work to date.

Authors: Gianna Milan, Andrew Rosenblum, Maria Sumareva, Inesa Gegprifti, and Akina Yura

- Jeremy Orosz, “The Twelve-Tone Music of Roque Cordero,” abstract, Latin American Music Review 39, no. 2 (2018): 137-159, muse.jhu.edu/article/717147.

- Marie Labonville, “Roque Cordero (1917–2008) in the United States,” (2011): 3-4, http://hdl.handle.net/2022/15513.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 5-6

- Carlos Espinosa-Machado, “An Analysis of Two Works for Orchestra: Adagio Trágico and Ocho Miniaturas by Panamanian Composer Roque Cordero” (DMA diss., University of Kansas, 2015), 13-14, https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/19441/EspinosaMachado_ku_0099D_13833_DATA_1.pdf;sequence=1

- Freeman, Paul. Columbia Records’ Black composers series, Vo. 4. New York City: CBS Special Products [1987], LP.

- Labonville, 15.

- Ibid., 7-8.

- ArkivMusic, “Roque Cordero – Overview,” http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Name/Roque-Cordero/Composer/2462-1#drilldown_overview

- Labonville, 7.

- Ibid., 15.

- “Composer Roque Cordero. A conversation with Bruce Duffie,” Bruce Duffie, transcribed 2020, http://www.bruceduffie.com/cordero.html.

- Labonville, 8.

- “Composer Roque Cordero. A conversation with Bruce Duffie”

- Ibid.

- Labonville, 7-8, 15-16.

- Thomas Carl Townsend, “A conversation with Roque Cordero,” LAMúsiCa 2, no. 4 (May 1999): 4-9, https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2022/14341/lamusicav2n4.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- German Gutierrez, “Cordero – Cantata Para La Paz,” October 13, 2017, Youtube video, 2:52-3:40, https://youtu.be/Pea8mOkfqxQ